The White Stripes, constriction and close-in innovation

Jack White, the musician behind The White Stripes, is well known for his devotion to black, white and red—adopting a career-long avoidance of the remainder of the color wheel. This might seem like a schtick or performance art, but in White’s own words, it’s quite purposeful:

“Telling yourself you’ve got all the time and money and colors you want, that just kills creativity. But constriction can force you to create.”

The White Stripes—notably just a drummer and guitarist—follows this methodology, forcing Jack and his band-mate Meg to do as much as they possibly can with the most stripped-down version of a band. Only what’s necessary. When I first heard Jack talk about constraint, it jived perfectly with my preferred path to product innovation: make the most of what you have. Some may interpret this as short-sighted or limiting, but I see it as exactly the opposite. It’s freeing, it’s focusing. It’s the difference between a “blue sky” boundless innovation approach that yields hundreds of half-baked Post-It Notes and a purpose-led approach born from the core of what a company believes in, is best at or is beloved for. The most successful innovations have one thing in common: they are novel tweaks to familiar formats. Creative takes on everyday constraints that ultimately move people toward preference and purchase.

How can you apply this thinking in your organization? Try using these two starting points as you approach innovation:

- Pay off your purpose—restricting ideas to those reflecting the brand purpose

- Do better at what you’re best at—limiting ideas to iterations on brand expertise

Pay off your purpose—restricting ideas to those reflecting the brand purpose

I was recently at Outdoor Retailer, the industry’s largest sports and recreation conference in the country, and was taken by the clear difference between brands focused on innovating from close-in vs. farther out, often unqualified stretches to simply be on trend. I’ll use two of my favorite booth experiences as examples of paying off the above innovation approaches. The most time I spent in any booth was at CamelBak, the brand famous for putting water-filled bladders on the backs of outdoor athletes. CamelBak is guided by a focused purpose: become the world’s leading maker of hydration solutions. And they’ve paid this off with specific hydration solutions for every sport, setting, and segment—from Military to mountain bikers to moms and their kids, each iteration perfectly suited for the activity or audience. The Reign line, for instance, features two waterflows bespoke to outdoor team sport needs: a shower spout to quickly cool the body and a jet spout to deliver fast hydration. The booth included walls on walls of truly unique twists on a seemingly simple task: drinking water.

Do better at what you’re best at—limiting ideas to iterations on brand expertise

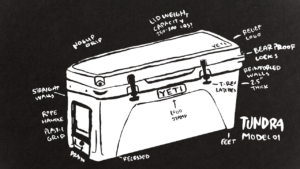

Then there is Yeti. Whether you classify Yeti as a cult or luxury brand, one thing is clear: it’s the best way to keep cold things cold. Yeti’s brand innovation begins with what it’s best at, and they’ve extended that expertise into an empire. People line up for blocks before Yeti store openings to shop what are elsewhere considered commodities, but now feel like superior solutions. Simple, focused, restricted to keeping cold things cold. Perhaps the clearest endorsement was Yeti’s own industry peers lining up for THEIR happy hour vs. others. A clearly moved audience after a simple insulated mug.

We often get lost in the word “innovation,” requiring ourselves to be revolutionary—obsessed with a flying car, when what we truly need is smarter cars on the road. We look so far into the future that we miss what’s right in front of our noses. When it comes to innovation, constraint births creativity. Next time you approach innovation, consider what (I think) Jack White once said, “necessity is the mother of invention.”

Want to talk smart stretches, close-in innovation, or debate The White Stripes’ best album? Contact Andy Woolard (awoolard@monigle.com)